Since September I’ve published a number of articles about the Periodisation Principles and Methodology of a number of inspirational coaches and academics. Although each coach has their own take or style of periodisation they all have a number of key features that I will summarise in this article, as well as drawing attention to where they differ (and in some instances why they differ).

This is the final instalment in my series about Periodisation (English spelling with an ‘s’, American spelling is traditionally with a ‘z’) and the methodologies from coaches that guided my early philosophies around periodisation of training seasons and event build ups. Have a read of last weeks article about Tudor Bompa and what he recommends his book Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training:

There are a number of benefits of periodising training. The biggest and most significant reason to periodise training is to ensure the athletes peak at the correct time or times of the year for the most important or significant events.

It also allows you to structure the training to develop all the attributes that an athlete requires (endurance, strength and power) appropriate for their events. By periodising the training these gains will be greater than if the athlete did not engage with a periodised training plan.

Periodisation adds variety to training and can increase enjoyment in the training, whilst simultaneously preventing performance plateaus.

From a coaching perspective it provides structure and a logical progression to the training.

There is a reduced risk of overtraining and burnout by the variety of stimuli it provides and it aids with injury prevention by providing opportunities for rest and recovery.

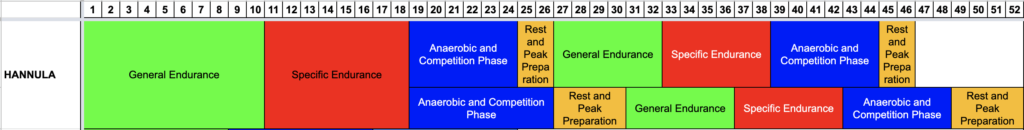

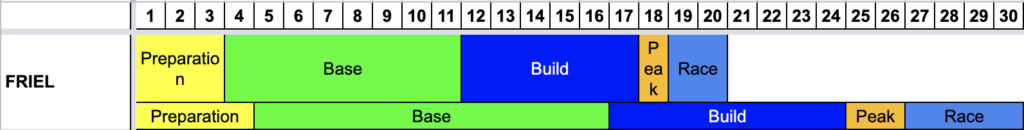

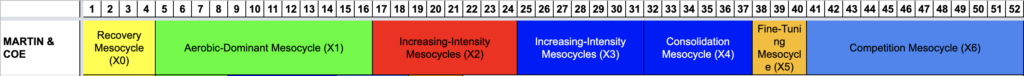

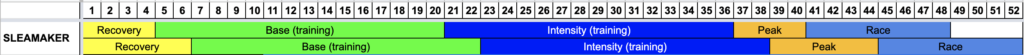

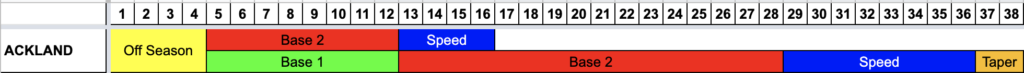

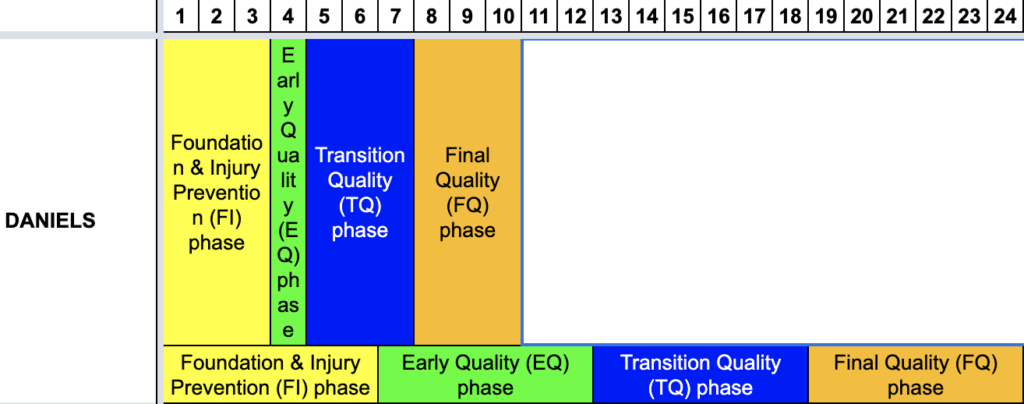

Throughout this article I will display example periodisation plans using the terms utilised by the coaches being discussed. I have colour coded each phase of training in a similar way so you, the reader, can see an overview of what training is included in each phase.

- Yellow – rest and recuperation, low key, low intensity, regenerative training.

- Bright green – aerobic focus, steady state, longer duration/distance training at moderate intensity.

- Red – aerobic focus with the inclusion of higher intensity work for the full duration of the phase.

- Bright blue (white white text) – speed or anaerobic focus that includes but not exclusively intervals or other forms of speed training at a higher intensity.

- Bronze – taper or early race season

- Dull blue – competitive phase, with the inclusion of higher intensity training.

There are typically two examples shown the top example being for a shorter more condensed build up and the bottom example being for a longer build up.

Where the coach’s name has a hyperlink this will take you through to the article I wrote about their periodisation principles and methodology.

Terminology

Macrocycle

A macrocycle is a complete build up for an event.

A full Annual Training Plan (ATP) could contain 1-3 macrocyles. Each macrocycle cycles through from the completion of one season/event to the completion of the next, and can be broken into smaller distinct stages.

The length of the phase will vary depending on the total duration of the build up.

Mesocycle

Each of the phases within the macrocycle are known as a mesocycle. More on these later.

Microcycle

Each mesocycle can further be broken down in to smaller units or blocks of training usually 6-10 days long, most frequently it will be a week. Depending on the athlete I’m working with occasionally I will use microcycles that are different from a week. For example some people working shift work cycle through their lives with 4 days working, 4 days off. For people like this I will typically use an 8 day microcycle (but have experimented with using a 4 day microcycle). Other people work 6 days and then have 4 days off, here I use a 10 day microcycle. But for the majority of us who work for 5 days and then have their weekend off, I use a 7 day microcycle.

Each mesocycle can have a wide amount of microcycles, some can be single microcycle long, others many microcycles (up to 30 in some instances but this is not typical).

Coaches & Academics

Sean P. O’Connor

First up I’m going to cover off Sean P. O’Connor because I don’t subscribe to his methodology, although I would recommend it in certain circumstances. Sean has made a name for himself as a the coach of the Boys Head Coach for Lafayette High School, MO and he wrote his book Distance Training Simplified.

He splits his season or build up into thirds and prepares his runners for events that are two distances longer and two distances shorter than their planned specialised race distance. For example if they are going to be a miler, the first phase of training will see them focus on 5km endurance and 400m speed. He refers to this phase as the Early (or Experimental) Season.

The phase covering the middle third is known as the Middle (or Mastery) Season and sees his athletes target the distance one above and one below their specialised distance. For example if they are going to be a miler, the first phase of training will see them focus on 2 mile endurance and 800m speed.

The final phase is known as Championship (or Compete) Season sees the athlete target their specialised event. Using the example above this will be the mile.

What I like about this methodology is that there is a lot of variety in the build up for the athlete. The athlete gets to experiment with different styles of events, as Sean gets his athletes to race longer and shorter events earlier in the season and as they get closer to the major championship events they start to hone in on their specialised event.

The traditional approach to periodisation is emphasised by Sean with the move from general to more specialised as the season progresses.

This approach to preparing training will work well with a group or a squad of athletes who are all building towards the major championship events at the same time. A group of high school or college athletes who are preparing for the state or national championships together would be a good example.

It would not work for a group of diverse age group athletes training for a wide range of events that occur at different times of the year (such as the group of athletes that I coach).

Tudor Bompa

The God Father of periodisation himself. Although he didn’t invent periodisation, he draws his knowledge from the early Eastern-Block researchers of periodisation and became a master of it. Everything else gets measured against what Tudor Bompa has written about periodisation in Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training and other texts on the subject.

The general principle of periodisation sees an athlete work through a number of phases with an initial Preparatory phase which can be further subdivided into General Preparation and Specific Preparation sub-phases. After the Preparatory phase the athlete moves into the Competitive phase which also can be sub-divided into Pre-Competitive and Competitive sub-phases. After the athlete has completed their competitive season they then move into a Transition phase where they rest up and get ready to commence their next cycle of training moving into their next season.

Within the Preparatory phase the endurance athlete will enhance their aerobic endurance. This can be commenced within the Transition phase but with more of a focus in the General Preparatory phase. This is achieved with steady state, moderate-intensity training to build and enhance the aerobic energy and cardiovascular systems. Volume of training increases to ensure the body has the opportunity to develop and adapt.

Training will progressively transition towards more specific endurance training by becoming more sport (and distance specific). Training will include intervals at a variety of intensities to progress the athlete, whilst still including training that will maintain their aerobic function already developed.

Swim Coaches

With the exception of open water swimming, the majority of competitive swimming is pool based and over shorter distances. Swimmers typically train in a squad based format and have very similar training programmes. The majority of the research and examples for periodising swim training, aren’t dissimilar to to middle- or sprint-distance runners, but still there are some similarities and principles that can be incorporated by endurance athletes.

Jill Sterkel

Jill Sterkel was the Woman’s Head Swimming and Diving Coach for the Texas Longhorn’s at the University of Texas at Austin for 16 years in the 90’s and 2000’s. She was also a gold medal winning Olympian in 1976 in Montreal and also achieved two bronze medals in the 1988 Seoul Olympics. She wrote the chapter on Long- and Short- Range Planning in The Swim Coaching Bible that is endorsed by the World Swimming Coaches Association.

Jill would start by dividing the season into phases. She used five different phases:

- Preseason,

- Aerobic Development,

- Anaerobic Development,

- Race-specific, and

- Competition.

The Preseason was all about getting the swimmer ready for the training that would follow, by building consistency and frequency of training.

Aerobic Development build the efficiency of the the cardiovascular and aerobic energy systems. Then the swimmer moved into enhancing the anaerobic system.

After that phase the swimmer got ready for the race season with specific training and that was followed with the Competition season.

Jill developed her swimmers progressively building the training load and intensity before tapering off.

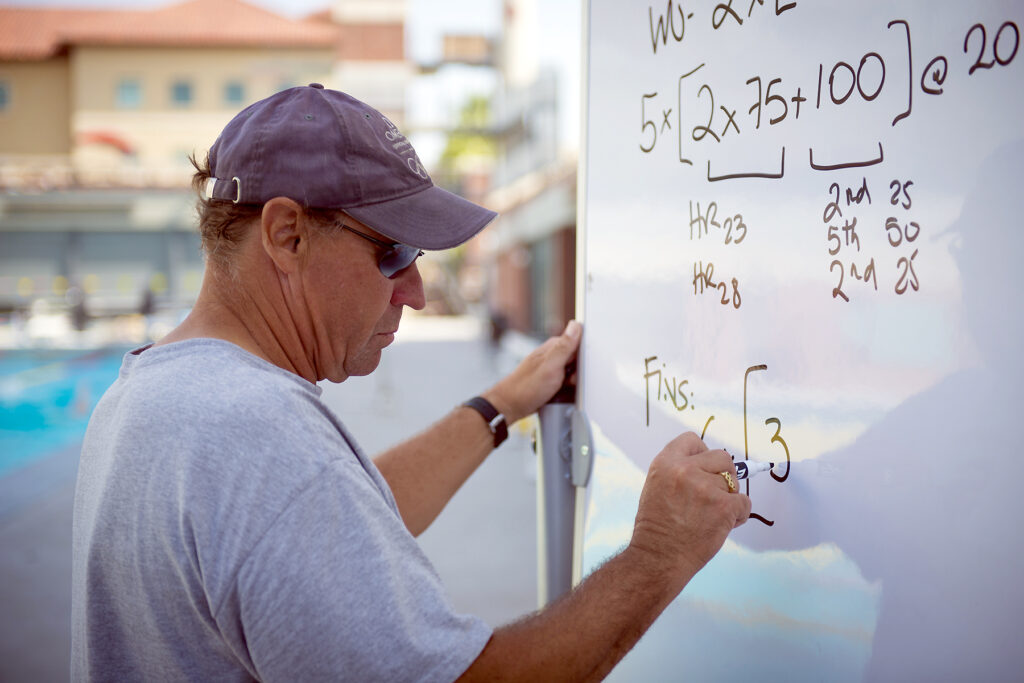

Dave Salo

David Salo is a swimming coach based in Southern California, United States. He was the head coach of the men’s and women’s swimming team at University of Southern California, as well as USC’s club team: Trojan Swim Club. Prior to his becoming the USC coach in 2007, he was the head coach of Irvine Novaquatics, a position he held since the fall of 1990, and was head coach of Soka University of America’s men’s and women’s swimming teams from 2003 to 2006. In his book with Scott Riewald, Complete Conditioning for Swimming, Dave Salo has a good chapter summarising how he structure’s a swimming season.

Dave’s five phases to a season are:

- Preliminary phase;

- Training phase;

- Competition phase;

- Championship phase; and

- Active rest phase.

Lasting a few weeks the goal of the Preliminary phase is to develop consistency in training, regain a feel for the water, as well as developing the warm up and precompetition routines, similar to to Sterkel’s Preseason phase.

The aim of the Training phase is to build a base level of fitness and muscular endurance. This phase will often involve the highest volume of training in this phase (both in the pool and dryland). Typically, this phase will last for six weeks , but an even longer block of training (8 weeks or more) can be better. This phase serves as the foundation to develop power and swimming specific strength. This is aligned with Sterkel’s Aerobic and Anaerobic phases. Both the Preliminary and Training phases fit into Bompa’s Preparatory phase.

The Competition phase is the main part of the competitive season building towards the major championships. During this phase training becomes more specific to the key events and strokes of the swimmers. There should be an emphasis on fast swimming every day and building race-specific speed and mechanics (such as stroke rates and cycle counts). There should still be an aerobic component to training, the focus is more on matching the intensity and work-to-rest ratio that replicate a race. This aligns with Sterkel’s Race-Specific phase and Bompa’s Pre-Competition sub-phase of his Competitive phase.

Then finally the Active Rest phase which allows the swimmer to have a mental and physical break from intense training. What is NOT is a time of phsyical inactivity. Aerobic exercise and cross training should be done to maintain a level of fitness. Dave Salo recommends swimming every second day to maintain feel for the water, but these can be low key, non-structured workouts. Water Polo is a great way of combining fun and swimming as a non-structured workout. This aligns with Bompa’s Tranistion phase.

Dick Hannula

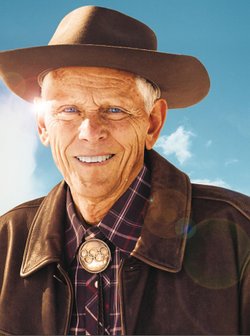

Dick Hannula is arguably one of the most successful swim coaches of all time. Under his leadership the Tacoma Swim Club won 24 consecutive state championships, a total of 323 swim meets with no loss!!! He was the US National Swim Coach multiple times between 1973 and 1985, as well as manager for both summer Olympics in 1984 & 1988. He has been inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame and is credited with developing the modern swim paddle with holes in them to facilitate feel for the water. He has authored Coaching Swimming Successfully and edited The Swim Coaching Bible.

When Dick Hannula plans a season he bases it around making a master calendar with the entire competitive schedule listed. As a club coach he would plan a full year with two competitive seasons – a short course, followed by a long course. However he acknowledges that some clubs may need a third season in the fall where they have swimmers peaking for a championship meet in order to qualify for meets later in the year.

Three years out of four the USA Swimming National Championship meet would be the most significant meet for the Tacoma Swim Club and in the fourth year it becomes the Olympic trials. This is what is known as a quadrennial plan leading into each Olympic year.

The aim of the General Endurance phase is to develop overall aerobic and fitness levels and lasts for ten weeks. After 4 weeks training Threshold training is gradually introduced to build to about 20% of total training over six weeks. Sprint training is also included daily but is very minimal totally no more than 5% of weekly volume.

Being eight weeks in duration Specific Endurance is the next phase of training. The goal of which is to improve aerobic endurance and maximise the anaerobic threshold, with the emphasis being in the swimmers specialty events. During this phase the weekly volume builds to a peak in the final weeks of the phase. After this overload peak, training levels are dropped back to the levels prior to the overload but intensity is increased. This will create supercompensation which is well placed to lead into the anaerobic phase. About 25% of this phase is made up of Threshold swimming (except during the overload phase where it is reduced to 15%). Speed training is gradually increased up to about 10% of training volume. Middle-distance and sprint swimmers will do about 10% less total volume than the distance swimmers.

Lasting six to eight weeks the goal of the Anaerobic and Competition phase is to develop speed with a focus on race-pace whilst maintaining aerobic fitness. For sprint and middle-distance swimmers this phase of training will see a shift to an anaerobic emphasis and for distance swimmers the focus is on race-pace and threshold swimming. Sprinting is increased for swimmers specialising in events shorter than 200m. Weekly milage is decreased through this phase and the first of the swim meets occur during this phase as well.

The Rest and Peak Preparation phase will typically last two to four weeks. The goal is to permit adaptation for peak performance. Volume and intensity are decreased. I personally disagree with decreasing intensity at this point in a season, I would maintain the intensity whilst decreasing the volume

Other Endurance Coaches

Arthur Lydiard

Arthur Lydiard was the fore-father of periodisation in run training. He developed his own methodologies in the 1950’s and 60’s that lead to his athletes winning a range of Olympic medals from the 800m through to the marathon with Murray Halberg, Peter Snell, Barry Magee and John Davies. Arthur’s methodology is often misquoted or interpreted wrong. He was well known for long runs for ALL his athletes and this is what he is most often remembered for, but he was equally insistent on speed work. Arthur wrote a number of books including Running with Lydiard.

It is during the Marathon Conditioning Training phase that Arthur aims to improve the efficiency of three factors:

- The ability to absorb oxygen from the air;

- Transport it to various muscles and organs; and

- Capacity to use said oxygen.

Results from this phase of training include a bigger and more powerful, it can pump more blood every beat and can also beat faster. Greater capillary beds within the lungs, which enables more oxygen to be absorbed more easily. Further more through sustained running for longer durations lays down more capillary beds within the muscles. This means that oxygen can be more easily delivered into the working muscle cells and exchanged for waste products to be removed from the muscle.

Towards the end of this phase Arthur recommends including some hill springing (or bounding), as well as steep hill running. Arthur put ALL his athletes through this phase regardless of whether they were 800m runners or marathon runners. He wanted to maximise the aerobic conditioning of his athletes, so that regardless of how fast the opening pace was in an event, they were more aerobically fit than the other athletes and could literally save their legs (by not developing lactic acid) for the kick to the line. His training schedules see this phase lasting as long as practicable before moving onto the remaining phases. This aligns with the General Preparatory phase of Bompa’s methodology.

In the Speed and Anaerobic Capacity phase of training Arthur tries to develop the capacity to exercise anaerobically and handle high oxygen debt. During this block of training the running will create fatigue levels which simulate your body metabolism to respond as a result of the level of effort. The marathon conditioning phase has built your stamina and you will be ready to begin developing your speed and increasing your anaerobic capacity (both elements which were avoided in the Marathon Conditioning phase of training). Hill springing continues throughout this phase as we aim to strengthen muscles, tendons and ligaments as well as put springiness into our calf muscles. Anaerobic capacity is developed through the inclusion of wind sprints of up to 400m. The distance is limited to avoid over doing things in this phase. Nor have diminished performance due to excess fatigue due to the build up of waste products like lactic acid. Arthur would alternate hills with wind sprints through the week and then have his athletes run long to round-out the week. Arthur states that this phase shouldn’t last longer than four to five weeks. This aligns with Bompa’s Specific Preparatory Phase.

With out developing the aerobic base in his Marathon Conditioning Phase, and then strengthening the body and exposing it to the wind sprints, this prepared the athlete for this final phase of training that built on everything that came before it. If that previous work wasn’t done, the results of going straight into the Track Training phase will be sub-par.

Speed is the primary importance in this phase. With that importance also come more intense, anaerobic activity. Arthur recommends fast, relaxed speed over distances of 100 to 150m, with Rest Intervals (RIs) of at least three minutes, so each run you can hit your maximal speed, time and time again. He also suggests holding back on your pace a touch, so that it can continue to be raised as you work through the session. Also included with in this phase are a range of workout styles that won’t be delved into in this article but all can and will play an important role depending on the nature of the event being prepared for. They include:

- Fartlek,

- Paarlauf,

- Time Trials,

- Repetitions,

- Sharpeners,

- Sprint training, and

- Starting practice.

The duration of this phase is for ten weeks prior to the major event that is being targeted, with the focus on the first 4-4½ weeks being on anaerobic capacity. This phase concludes with a tapering off of the training with the last hard effort 10 days prior to the event. This aligns with Bompa’s Competitive Phase.

Joe Friel

Joe Friel is an elite level triathlon and cycling coach who has literally written the bible on training for both sports. He has a Master’s Degree in Exercise Science and has coached Olympian’s and Ironman champions. His successful line of Training Bibles have been a staple on my bookshelf since the early editions:

Joe’s macrocyles can be broken into 6 distinct stages:

- Transition (post-season)

- Preparation

- Base

- Build

- Peak

- Race

The length of the phase will vary depending on the total duration of the build up. Friel’s philosophy is based on that of Tudor Bompa (the godfather of periodisation) where the season starts with more generalised training and builds towards being more specialised as you move towards the main events of the season. But as Friel says, “it involves arranging the workouts in such a way that elements of fitness achieved in an earlier phase of training are maintained (principle of reversibility) while new ones are addressed and gradually improved (principle of progressive overload)“.

The Transition phase is is 1-6 weeks to recover from the previous season or major event prior to commencing the main training build up. It allows you to unwind and freshen up after a demanding event. There is obviously a direct correlation with Bompa’s Transition phase.

3-4 weeks long within the Preparation phase you prepare to train. Effectively you are commencing the build up for the next season/event. The main focus during this phase is endurance, done at lower intensities and through a range of modalities, you can include cross training in addition to swim, bike or run training depending on your sport. Aspects of this align with both Bompa’s Transition phase, as well as the early General Preparation phase.

Overall the Base phase takes between 8-12 weeks and can be further sub-divided into three distinct phases. The main focus of this phase will be on endurance. Further development of Force training will initially continue from the Prep phase but will taper off prior to commencing Base 2. Some athletes that have a specific need to continue Force training can continue to do so right through the season.

During the Base 1 sub-phase will see a continuation of endurance training at lower intensities and with the inclusion of cross training like mountain biking. Complete the last of the Force training session within this phase of training. Through out the Base 2 sub-phase, Endurance training continues to get longer and cross training is eliminated as training becomes more race like in duration. This is when you would start to include Muscular Endurance training with longer periods at Level III intensity. Within the Base 3 sub-phase, endurance training continues to progress from Base 2. Muscular Endurance training continues through this phase with an increase in intensity to Level IV and Level V for shorter periods with an even shorter Rest Interval (RI) separating the work efforts. The Base phase aligns with Bompa’s General Preparation phase.

The Build phase will typically last between 6-8 weeks and will see an increase in intensity, a focus on weaknesses and maybe the inclusion of some lower key events. It two can further be subdivided into a couple of further sub-phases. As we move through the build phases Muscular Endurance efforts will have progressed to 20-40 minutes of non-stop efforts at Level IV. Within the Build 1 sub-phase Anaerobic Endurance for athletes this is appropriate for can be included through both Build 1 & 2, the duration of intervals is quite short and the recoveries longer still, but the intensity is very-high. Then during the Build 2 sub-phase, Anaerobic Endurance intervals can be done at a higher intensity (and shorter duration) for athletes that it is suitable for. Training to develop maximum Power can be included during this phase as long as it doesn’t compromise other components being trained and prepared. This aligns with Bompa’s Specific Preparation sub-phase within the Preparatory Phase.

The Peak Phase is where we can look to fine tune our performance by tapering off our training and consolidating race readiness with further events that are of lesser importance than the main goal of the programme. It’ll last only a couple of weeks at most. This aligns with Bompa’s Pre-Competitive sub-phase.

The final phase of the programme will include the most significant events of the season/build up and last no more than a few weeks. Obviously this aligns with Bompa’s Competitive sub-phase of the Competitive phase.

Peter Coe & David Martin

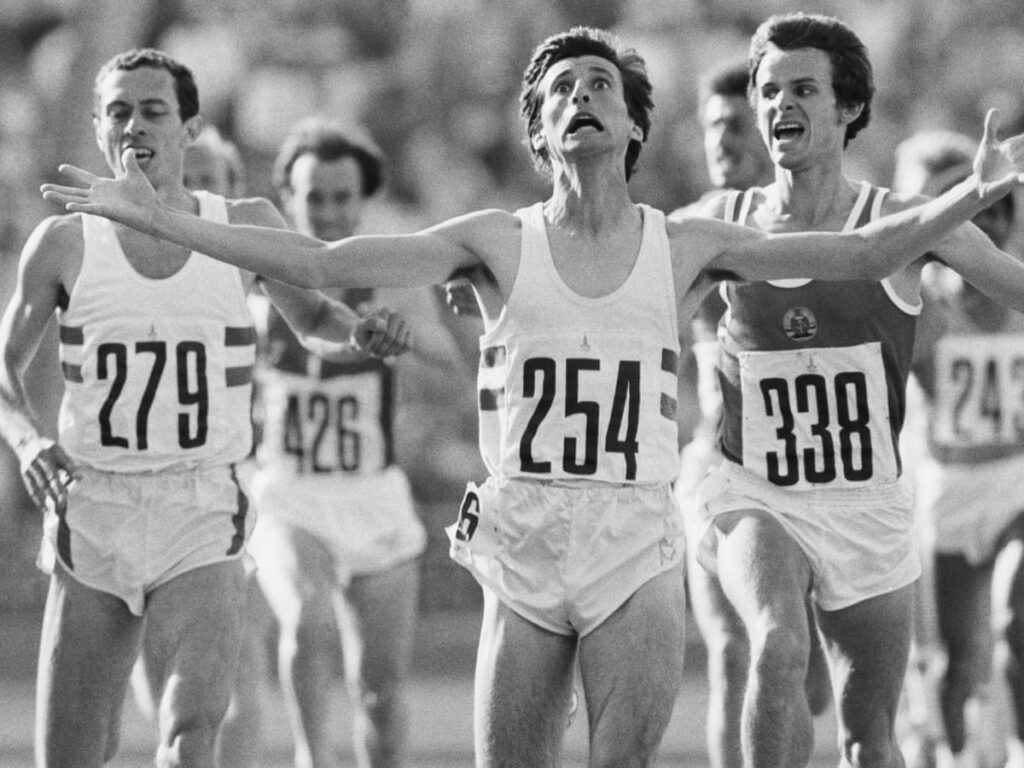

Peter Coe started out dissatisfied with the coaching advice Sebastian was receiving from his local club (this was based around the methodologies for Arthur Lydiard). Fluent in German, Coe senior translated the books of prominent German coach Woldemar Gerschler. Gerschler was a pioneer and proponent for Interval Training back in the 1930’s. His methodologies called on a pace “so fast that the pace required in competition would seem moderate and achievable”, and this is a key principle that Coe senior used to build the fitness of Sebastian Coe to win Olympic gold medals in the 1,500m in both Moscow and Los Angeles, combining that with silver medals in the 800m in the same Olympics.

Dr David Martin was a physiologist who specialising in pulmonary, cardiovascular, and exercise physiology. He was publicly acknowledged by both silver medalist Meb Keflezighi and bronze medalist and Deena Kastor in the mens and woman’s marathons respectively at the 2004 Athens Olympics for his input and advice for their success.

Peter Coe and David Martin co-wrote Better Training for Distance Runners and it is from here that most of their methodologies around periodisation come from, which are in contrast to other articles I’ve written in this series.

Martin and Coe describe periodisation with their Multi-tier training like building a multi-level house or building. You need various building materials (aerobic and anaerobic running, comprehensive conditioning, flexibility etc…). Several of the materials (training intensities and modalities) should be utilised in an ongoing fashion to complete the goal of a finished building (or a competitively fit athlete). Depending on the progress of the construction, the relative mix of ingredients will cary. They describe an expert in periodisation as having a similar job to a building contractor. As both are responsible for arranging the availability, quantity and pattern of use of all the various components for completing the task at hand.

They have seven levels or tiers in their multi-tier training:

- X0 – Foundation of full recovery

- X1 – Establish aerobic base

- X2 – Increasing intensity 1

- X3 – Increasing intensity 2

- X4 – Consolidation (confirming)

- X5 – Event fine-tuning

- X6 – Competition – tapering off for the ultimate goal

These coincidently align with both Lydiard (who Peter in particular was so disillusioned about) and Bompa, with X1 aligning with Lydiard’s Marathon Conditioning Training phase; X2 & X3 aligning with Lydiard’s Speed and Anaerobic Capacity phase; and X4 & X5 aligning with Lydiard’s Track Training phase. When compared with Bompa’s mesocycles X0 aligns with the Transition phase; X1 aligns with the General Preparation sub-phase; X2 & X3 align with the Specific Preparation sub-phase; X4 & X5 align with the Pre-Competition sub-phase; and X6 aligning with the Competition sub-phase.

Peter and David define multi-tier training as several layers or tiers of training, each of which builds on the previous one. Each tire has a specific and different developmental focus. With the overall development creating a well-rounded performance. They describe periodisation with their Multi-tier training like building a multi-level house or building. You need various building materials (aerobic and anaerobic running, comprehensive conditioning, flexibility etc…). Several of the materials (training intensities and modalities) should be utilised in an ongoing fashion to complete the goal of a finished building (or a competitively fit athlete). Depending on the progress of the construction, the relative mix of ingredients will cary. They describe an expert in periodisation as having a similar job to a building contractor. As both are responsible for arranging the availability, quantity and pattern of use of all the various components for completing the task at hand.

Multipace training is very fundamental to the multi-tier system. Long-distance runs of moderate intensity build aerobic endurance. Fast-paced longer-distance running improves stamina. Very-fast, short-distance running improves strength and quickness.

A 1,500m specialist needs 5,000m distance-training as well as 800m speed training. A 10,000m specialist can benefit from a periodic very long run (although no as long as those done by a marathoner), but needs some of the speed training of a 5,000m runner as well. Training at the primary-event race pace teaches awareness of the event itself.

During a full macrocycle (a complete training period or season, typically a year) the entire building will be constructed (to continue using the building analogy). Each level of the building is represented by a mesocycle or a teir. Thus, a multi-tier training plan with several mesocycles or levels each of which has a different assigned goal for athletic development. The length of each mesocycle may vary depending on event requirements, fitness of the athlete and time available.

The Recovery Mesocycle (X0) is a restorative period of general activity (alternative training that will maintain a semblance of fitness without specific run training) and is aimed at assisting recovery (mental and physical) from the previous microcycle/season and get ready for the next season/macrocycle. Duration 4 weeks (for a 52 week macrocycle).

The purpose of the Aerobic-Dominant Mesocycle (X1) is to develop anaerobic base. Inclusion of a single, appropriate speed-work session (or low-key race) ensures the multipace approach. Duration 12 weeks (for a 52 week macrocycle).

The emphasis in the Increasing-Intensity Mesocycles (X2, X3) is on higher-quality training intensities. Faster-aerobic work as well as anaerobic training. Close attention to monitoring total training load, to ensure adaption is successful by not over-doing either volume, intensity or density without excessive fatigue. The volume of aerobic load will gradually decrease to keep the total load manageable. Duration 8 (X2) and 7 (X3) weeks respectively (for a 52 week macrocycle).

Within the Consolidation Mesocycle (X4) is the time to identify which training modalities may not have come-on or developed as desired. This is the mesocycle to r-target and further enhance these training modalities that are needed. Duration 6 weeks (for a 52 week macrocycle).

The Fine-Tuning Mesocycle (X5) is the phase where finishing touches are added to the training. This is the time to further develop any specialist skills for the athlete and event. Training is greatly decreased in this phase of training to ensure a well rested athlete arrives at the Competition phase prepared to run FAST. Duration 3 weeks (for a 52 week macrocycle).

As with the previous mesocycle training is greatly reduced in the Competition Mesocycle (X6) but it continues on each aspect of training. Duration 12 weeks (for a 52 week macrocycle).

Rob Sleamaker

Rob Sleamaker is a sports physiologist with a Masters of Science (MS) degree who developed his SERIOUS Training System back in the 1980’s. This is more holistic approach to training, where his overview targets, not just Physical Preparation, but also Technique, Nutrition, Equipment and Mental Skills to develop overall Optimal Performance. He is the author of one of the very first books on endurance training: SERIOUS Training for Endurance Athletes.

An entire competitive season is made up of five training stages:

- Base (training) – 16 weeks,

- Intensity (training) – 16 weeks,

- Peak – 4 to 6 weeks,

- Race – 8 to 12 weeks, and

- Recovery – 4 to 6 weeks.

The number of weeks can and will vary but the example weeks given there are typical for an athlete preparing for a a competitive season each calendar year. Within each of these stages or phases of training Rob would periodise the intensity and volume to fit the goals of each stage.

After a long build up and/or racing season any athlete will be a bit stale, weary and/or unmotivated. It is important to have a period of active recovery following any season, hence this Recovery stage. Reduced training load with low-intensity exercise and alternative sports common in this phase, there is certainly no need to have high intensity training included in this stage. This aligns with Bompa’s Transition phase.

The primary focus within the Base stage of training is to build an aerobic foundation and what Rob refers to as a “plumbing system” which is a reference to the cardiovascular system, as well as lung capacity. With as an efficient aerobic engine built your body will be in a position to support high-intensity training and racing later in the season. The bulk of the training conducted during this phase is predominantly over-distance training, with an appropriate amount of strength development. High-intensity training during this phase is limited. The key developments that will occur as a result of this training intensity are improving fat oxidation, improving the muscles blood capillary density and mitochondrion number and efficiency. These are all significant contributors to improving oxygen transport and energy use at the cellular level. General muscle strength as well as sport specific strength are also emphasised during this phase of training. This is to increase the force per contraction of prime mover muscles. This aligns with Bompa’s General Preparation sub-phase.

The overall aim of any training plan is to make the athlete faster, by maintaining higher-intensity effort for longer periods of time. This can not occur without the inclusion of intensity: intervals, speed and race/pace efforts. During the Intensity stage of training the overall training stress increases by virtue of a higher training volume and also higher intensity. Elements are added gradually throughout the stage so the body can adapt appropriately. Overdistance and endurance/easy intensity training still makes up the bulk of this stage of training to maintain the aerobic base established previously. Too much high-intensity training or racing at this point may lead to premature peaking or burnout. This stage aligns with Bompa’s Specific Preparation sub-phase.

Whether called Peak, tapering or sharpening this stage of training is to get you ready for “show time“. Physically ready, mentally ready, well rested. The Peak stage sees a decrease of training volume, but not a decrease in intensity. Rob describes the intensity as very high in certain workouts “to refine technique and energy systems“; I prefer to describe the intensity in this phase as specific because “high” or “very-high” might not be appropriate think and Ironman or Ultra-distance athlete. Rob is referring to intensity compared to race intensity being race-like, but High or very-high intensity can be misleading, implying it could or should be higher than race intensity. Meanwhile, overdistance and endurance/easy intensity training are still present in this phase to maintain the aerobic base established previously. There should also be an emphasis on restoration and recovery during the taper stage, so that the body is fully rested and energy stores are maximised prior to intense competition. This stage aligns with Bompa’s Pre-Competition sub-phase.

By the point of arrival at this stage your body should be highly tuned and in optimal racing condition., hence the Racing stage. A large portion of this stage is still dedicated to overdistance and endurance/easy intensity to provide active recovery as well as maintain the aerobic base. With the rest of the phase constituted by intervals, speed and racing. Restoration methods such as massage, relaxation, proper nutrition and hydration and consistent rest are equally important as any physical training completed. This aligns with Bompa’s Competition sub-phase.

Jon Ackland

Jon Ackland was an early inspiration of mine. It was possibly him who first introduced me to the term Periodisation through articles in NZ Triathlon magazines in the early to mid 90’s. Then in the early 2000’s I attended a number of seminars he held about Ironman preparation and took on a lot of his philosophies from these seminars.

In his books The Power To Perform: A Comprehensive Guide to Training and Racing for Endurance Athletes and Personal Best: Secrets to Success in Sport from Beginners to Winners both of which I believe are now out of print, as well as he discusses in great detail the process for periodisation. And in Precision Training he employs these concepts into over 100 training programmes for a range of sports. Jon established Performance Lab – which delivers a range of coaching and performance services and now Arda which is software company that provides virtual coaching through wearables.

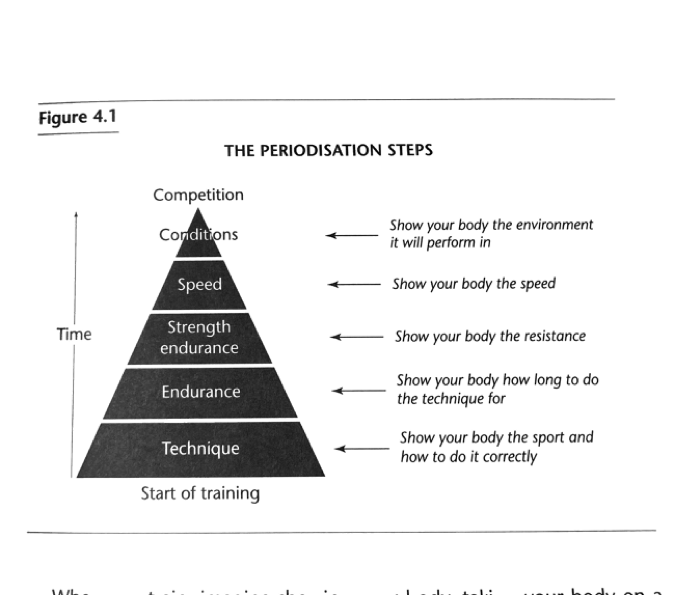

Periodisiation is a method for structuring training through a season leading to a race or an event. it has been a concept that is grown in scope and developed over the decades to the modern era.

Jon describes it as a logical conversation with your body:

- Show your body the Sport;

- Show your body the Skills;

- Show your body the Distances or Duration;

- Strengthen your body up;

- Bring in the Speed and the Specifics; then

- Show your body the Terrain, the Environmental Conditions, the event Atmosphere and Pressure, and the Course

This can be summarised in a chart from Personal Best.

Jon breaks a season or build up into three key phases or blocks of training:

- Pre-Season,

- In-Season, and

- Off-Season.

They loosely are the build up, the competition and the recovery.

Once you’ve raced your season (however long it was), the aim now is to recover from everything you’ve done thus far. This period may last four to six weeks in length. Jon expands on the reason for this duration, as most people will cease to feel muscle aches and pains from their event (even if it’s an Ironman) after about a week of minimal or no training. This season is all about mental recovery, a break from the routine and structure of the proceeding build up. Some athletes are worried about loosing performance through taking a break. Yes there will be a small performance loss, but you will be mentally and physically prepared to come back stronger. During this period mix things up and try different activities and be guided by the these three words: relax, forget, unwind. This aligns with Bompa’s Transition phase.

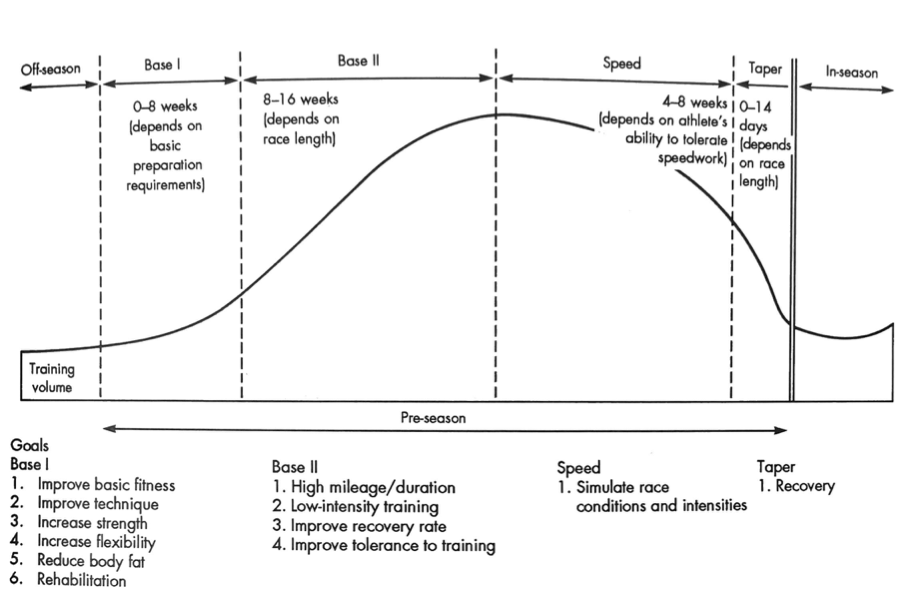

Pre-Season is all about preparation and gradually introducing your body to everything that will happen on race day in order to get and to be ready for the event. This will last for eight to sixteen weeks and may include several smaller events in the build up. The three secrets for this phase are: preparation, preparation and – you guessed it – preparation. Pre-Season can be broken down into sub-phases that Jon refers to as Base, and Speed Phases. Base training forms a foundation of fitness and speed training prepares you for the demands of racing.

The Base Training phase can last as long as six months, but this will depend on the length of your build up and how much time you have available before your event, as well as your level of fitness when you commence this build up. This phase will mainly consist of high milage/long duration workouts at a low intensity. The aim of these sessions is to improve your aerobic ability and muscular endurance. As you work through this phase, your tolerance to exercise improves as you adapt to the training load. You will recover quicker and this base work will allow you to cope and adapt to the speedwork that will follow.

Base training itself is split into two phases Base 1 and Base 2. Within the Base 1 sub-phase:

- Show your body the Sport;

- Show your body the Skills;

The goal of this phase is to prepare your body to the type of exercise you are planning to compete in. This is also the time to work on technique, improve strength and flexibility, reduce body fat and rehabilitate from injury.

During Base 2 sub-phase volume is gradually increased. Training is still done at a low intensity, although small amounts of speedwork can be included. How much milage should this phase include? That will depend on your ability. If you are new to the sport your capacity for work will be less than that of an experienced athlete and your recovery from each workout will be slower. Keep in the back of your mind when you read a pro-athletes training programme, it’s taken them years of training to build to that amount of volume. Jon recommends splitting Base 2 sub-phase into three further parts. During the first third of this block of training keep things very easy. In the middle third include hill training and then towards the end of the base include up tempo training. This will help you prepare for the speed phase.

- Show your body the Distances or Duration;

- Strengthen your body up;

The Base phase aligns with Bompa’s General Preparation sub-phase.

The Speed Training phase follows the Base Training. Now is your opportunity to take advantage of the fitness you have developed in the Base Phase. This phase will last four to eight weeks and this is where your performance gains are made. In this phase training volume decreases and intensity is gradually added into the training. Allowing the body to adapt to this higher workload progressively. There are a number of ways to include speedwork into your training from intervals, time trials, sprint training and event low-key events/racing. Too much speedwork and your could get injured or overtrained, not enough speedwork and you will under perform at your event. This phase also needs plenty of recovery built into it. Make sure that you do your slow sessions slowly, so that when it comes time to HAMMER your speed sessions you can.

- Bring in the Speed and the Specifics; then

- Show your body the Terrain, the Environmental Conditions, the event Atmosphere and Pressure, and the Course

The Speed phase aligns with Bompa’s Specific Preparation sub-phase.

The last two to fourteen days of the Pre-Season are set aside for a Taper/Peaking. This is where the training volume is eased back to allow your body to freshen up. For events that are about an hour in duration two to four days is probably enough time. But for an Ironman two weeks is probably best. marathon tapers are typically about ten days. A common mistake with a taper is that you remove the intensity out of your training, this is important to maintain the intensity just reduce how much you do of it (or have more recovery between reps). The Taper/Peaking phase aligns with Bompa’s Pre-Competition sub-phase.

The competition season is not always used. For big events (read long-duration), the In-Season maybe the day of the event only. For shorter events you may choose to race regularly over a period of between four and twelve weeks. This season is not about training to improve but training to maintain performance. Jon summarises this as the Pre-Season is about train, recover, train again; and the In-Season is about race, recover and race again. Unfortunately, you can’t maintain peak performance year around. Training has to be based around a group of goal events per year. Jon uses the example of four to eight short events being tolerable for most athletes, for longer distance events this drops to one to two events. Yes, there are examples out there of athletes that do many more, but I’d suggest they are not racing nor training optimally to get their best performance. Obviously this aligns with Bompa’s Competition sub-phase.

Julian Goater

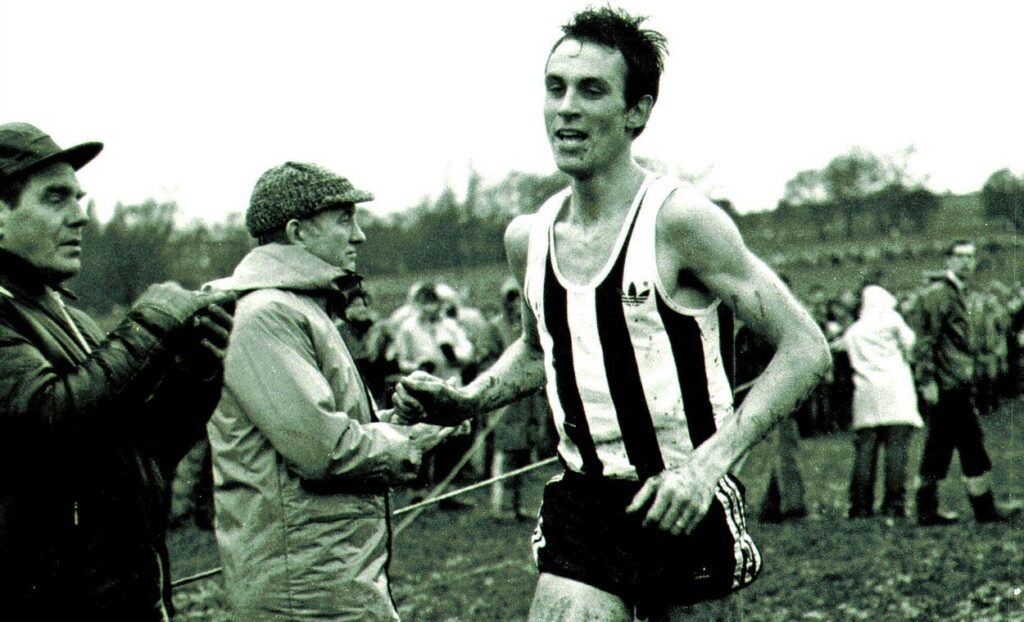

Julian Goater was a top British athlete winning a gold medal with the rest of the British team at the World Cross Country Championships in 1979. He has a 5,000m PB of 13:15.59 and a 10,000m PB of 27:34.58 (which to this day is a still in the Top 10 fastest UK times ever). In more modern times Julian is now running a coaching company in the UK called Feel Good Factors for runners and cyclists. In his book he wrote with Don Melvin The Art of Running Faster Julian talks about his methodology of periodisation.

Julian Goater describes periodisation as “training differently during different periods of time, in progressive steps towards full readiness to race your best on the day in question.” There doesn’t need to be a radical change from one period of training to the next, in fact keeping your keeping the basic structure of your weekly training the same will be advantagious.

During the week you will still run 4-5 key sessions:

- A long run;

- A fartlek session;

- Some sort of repetitions (either on hills or the flat); and

- At least one steady, recovery run.

Periodisation introduces a subtle change of emphasis. It involves dividing your training into six distinct phases of training. Julian Goater calls these phases:

- Active Rest (4 weeks);

- Basic Conditioning (4-6 weeks);

- Endurance Base (8-10 weeks);

- Quality Training (6-8 weeks);

- Race Preparation (4-6 weeks);

- Competition Phase

The Active Rest Phase is a break from last seasons training and racing. Goater recommends that you stay active during this phase to avoid turning into a blob. Keep training unstructured without putting any pressure on yourself training wise. This aligns with Bompa’s Transition phase.

The Basic Conditioning phase builds your overall strength and makes you more resilient. This is an opportunity to develop your weaknesses and also to progressively build your mileage up.

Within the Endurance Base phase you will continue to build your mileage to a very, high level. This level is relative to what you’ve done in the past. Julian also recommends that you don’t plod and incorporate a mix of intensities within these runs. Both the Basic Conditioning phase and Endurance Base phase align with Bompa’s General Preparation sub-phase.

During the first three phases, you shouldn’t be desperately seeking top fitness but more letting the fitness come to you. The point of these phases is that you are getting fit enough to train hard.

Within the Quality Training phase of training, your intensity will be more intense than any other phase of training (whether hill reps, track work or fartleks). This is where training gets specific (after the good preparation you’ve already put in). Here your target race(s) will assist determine the style of session and the pace involved. The shorter and faster your race the shorter and faster your repetitions will be, and there will also be more rest to ensure you can maintain the speed in the coming reps. Conversely, the longer your race is, the longer your repetitions will be, and you won’t be holding as fast a pace, with less requirement to have longer Rest Intervals (RI). This aligns with Bompa’s Specific Preparation sub-phase.

The Quality Training Phase with its intensity and maintaining a highish mileage will make you fit, but it won’t make you ready to race. With the fatigue of so much training you can’t race at your best. The Race Preparation Phase is designed to get your ready to race. You will still train intensely, to maintain your leg speed and ability to run whilst out of breath. But you can also practise tactics, pace judgement, and changes of pace. Mileage will be reduced in this phase so that you are fresh, fit and fast come the last phase of the training cycle. This aligns with Bompa’s Pre-Competition sub-phase.

The dilemma of the Competition Phase is to stay in top condition without making yourself too tired to race at your absolute best. This aligns with Bompa’s Competition sub-phase.

Julian’s principles of periodisation take you through a journey of preparing to train, preparing to train fast, before training fast and cutting back on the duration/distance as your prepare to race before finally you get to race, race at your peak performance.

Jack Daniels

Jack Daniels PhD, is an iconic American Running coach, whose successful series of books Daniels’ Running Formula now in its Fourth edition has become my bible when planning or periodising an athletes season. Jack Daniels competed and medalled at both the Melbourne and Rome Olympic Games in 1956 and 1960 respectively, as well as being named the World’s Best Coach by Runner’s World.

The season is broken into four phases, arbitrarily Phase I, Phase II, Phase III and Phase IV. They are always conducted in sequence. The first phase is focused on Foundation & Injury Prevention (FI) phase, the second is Early Quality (EQ) phase, the third Transition Quality (TQ) phase and the fourth being Final Quality (FQ) phase.

Daniels prefers to have a 24 week build up to any event but as we all know the perfect world doesn’t always exist and I’ll cover how he modifies a shorter build up later. With a 24 week build up that is 6 weeks for each phase.

The focus of the Foundation & Injury Prevention (FI) phase is to develop cellular adaptations, as well as minimising the risk of injury by preparing the body for the phases that follow. As the athlete works through the season the benefits of longer, steady running maintain physiological adaptations, even if there is less of this type of running occurring. Regardless of the distance being trained for the main emphasis in this phase is relatively easy running with the occasional inclusion of strides. This aligns with both Bompa’s Transition phase and General Preparation sub-phase.

The goal of the Early Quality (EQ) phase of training is to move the runner from the the raining they have completed through to the next phase, setting them up for success. This phase will introduce faster workouts after the FI phase. Any speed work should have an emphasis on good mechanics with 200/400m reps conducted at about mile pace with plenty of rest suitable in most cases. Marathoners can focus on anaerobic reps or VO2 max intervals, with a secondary priority on threshold efforts, but don’t forget the long runs as they are essential to success. Middle distance runners, as well as runners racing between 5km to 15km should have their primary focus on anaerobic reps or hills, with Threshold efforts also of secondary focus and VO2 max intervals next on the order of importance. This phase bears some resemblance to late in Bompa’s General Preparation sub-phase as well as his Specific Preparation sub-phase, merging between the two of them.

The Transition Quality (TQ) phase is the most stressful phase of training and should include workouts that build on what you’ve already accomplished in the earlier phases, weeks and months. As well as providing a good transition into the Final Quality phase of training. The idea is that you optimise the components of fitness most relevant to your event(s). By this stage of your build up you should have built your fitness, but don’t get caught up with your ego right cheques your body can’t cash……keep to the programme work hard, work smart but don’t over do it. The last thing you need during this phase is an injury, as the time to recover from it and rebuild your training is limited. Workouts of importance during this phase for a marathoner are VO2 max interval or threshold/long runs, with marathon race pace being less important during this phase. For athletes bracing between 5km and 15km VO2 max interval sessions are your priority, followed by anaerobic or hill reps, with long runs to maintain your aerobic function. Middle distance runners your primary emphasis should be VO2 max interval sessions, secondary importance should be anaerobic reps with threshold runs being the next tier of importance. This aligns with Bompa’s Specific Preparation sub-phase.

The Final Quality (FQ) phase of training prepares the body for the specific demands of the event. During this phase you will likely include threshold running, some reps or intervals and races in which you are attempting to perform optimally. This is also the time to focus on and further enhance areas of your running that you are already strong in. Quality workouts within this phase will vary depending on your goal. Marathon runners should focus on threshold or race pace running, with workouts designed to maintain your threshold ability, as well as continuing your long runs. Whereas athletes running 5km to 15km (including cross country runners) should focus more on threshold with some VO2 max and anaerobic rep runs to focus on the sustained speed. And middle distance runners should have a primary focus on anaerobic repetition training, with threshold runs of secondary importance followed by VO2 max running. This aligns with Bompa’s Pre-Competition sub-phase whilst also showing similarities to what would be included late in Bompa’s Specific Preparation sub-phase.

Rather than explain and detail Jack Daniels’ reasoning, (you can read it in his book any way) I’ve simplified his chart that is confusing to interpret initially. Depending on how many weeks you have to prepare for an event here is the number of weeks typically included into each phase of training. I say typically as you can always include more or less to provide an athlete the chance to develop their weakness.

| Weeks to the Event | FI Phase | EQ Phase | TQ Phase | FQ Phase |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 7 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 8 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 9 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| 10 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 11 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 12 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 13 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 14 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 15 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| 16 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| 17 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| 18 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| 19 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| 20 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| 21 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| 22 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| 23 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| 24 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

I’ve taken Jack Daniels’ methodology and modified it, adapting it for triathlons, as well as employing it for running and cycle training.

Summary

Overall most coaches periodisation principles align with traditional methods. There is room for flexibility within periodisation principles, especially around specific components of fitness building towards either key events or a season worth of events. Durations of different phases need to be adaptable to ensure that the objectives of the phase(s) are met and the athlete is optimally prepared.

I’m very excited to be speaking at USA Triathlon’s virtual Endurance Exchange conference this 3rd March! Endurance Exchange is the USA’s largest endurance sports conference, providing learning, networking and growth opportunities for coaches, race directors, officials, athletes and more. I’ll be talking about Periodisation/Periodization. Can’t join live? All sessions will be recorded and available to view on-demand. Learn more and sign up now at EnduranceExchange.com. Hope to see you then! #EnduranceExchange